| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: March 23, 2022.] Russ Roberts: Today is March 23, 2022 and my guest is Dwayne Betts. His first appearance on EconTalk was October, 2020 when he talked about reading, his time in prison, his poetry collection entitled Felon and his project, which is now called Freedom Reads, which has the goal of placing a curated 500-book collection in prison housing units so that curious prisoners can have access to books. And, since he was here the first time, he has won a MacArthur Grant. And, although we don't want to believe that correlation is causation, you never know--could be true. Russ Roberts: After EconTalk, everything turned around for Dwayne. Just kidding, but I am thrilled about that project, Freedom Reads. And, if you have not looked into it, we'll of course have a link to the website. I just want to warn parents listening with young children, there will be topics and conversation in this conversation that might not be appropriate for young children. So, you may want to listen in advance. Dwayne, welcome back to EconTalk. Dwayne Betts: It's a true pleasure. I'm really happy to be here. It is funny, because the sort of rub against economists is that they don't read books--literature--and you're consistently proving that not to be the norm. So, I'm excited to be here to talk about Primo Levi and Ralph Ellison. |

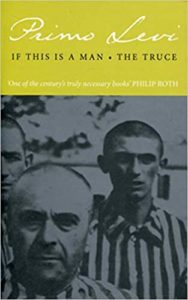

| 2:08 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. Well, the idea behind this conversation is a little bit crazy. I encouraged Dwayne to read two books by Primo Levi that I had read a long time ago. At least one of them, the first one, and that is a book called If This Is a Man, which is his memoir of being in Auschwitz. And, about a decade plus after he wrote that first book, he wrote a sequel, sort of, of what happened after he was released from Auschwitz, called The Truce. I'll mention in passing: they have different titles sometimes in America. The first, If This Is a Man is also called in America, Survival in Auschwitz. And, The Truce, I think is sometimes called in America, The Awakening. Those are both horrible titles. Primo Levi's original titles are much better. We'll probably talk about that. Anyway, so Dwayne read those, and I thought it would be interesting--they're about the Jewish experience to some extent--so I thought it'd be interesting for me to read something from the black experience and then we would share our thoughts on that. And, Dwayne suggested Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison, which I had 40 or 50 years ago, remembered very little of it. I particularly forgot it was 582 pages long. I might have made some kind of protest, Dwayne; but I'm really glad I read it. It's an extraordinary book, I think easily, arguably, the Great American Novel. And, I didn't appreciate it when I was 20 years old. And so, I'm very glad I read it again. Let's start--Dwayne, why don't you say something about Ralph Ellison? Dwayne Betts: Ralph Ellison is almost like the patron saint of missed deadlines because--and I'll talk about Invisible Man in a second--but he is the kind of person who put a lot of pressure on himself to write the first book. From Oklahoma, was a musician, but was just like a deeply curious individual. And, he moves to New York to become a writer. And, he builds these relationships with Langston Hughes, with Richard Wright--had a series of deeply, deeply fascinating letters with Richard Wright, which arguably helped me understand better some of the parts of Invisible Man that made me cringe on the first read and the second read. But, he would work on Invisible Man for years and years and years. And, when it was finally released, interestingly enough, the prologue and epilogue were written last, so it wasn't this notion of, like, he knew where he was going from the beginning. It's almost like a improvisational jazz riff. And, I always thought about it as a coming-of-age story, but it might be better considered a picaresque than a coming-of-age story. And, I stole that from somebody; but I think it might be better considered to picaresque because it is like sort of his work trying to understand what it means to be American. And, after that, he wrote, he excelled as an essayist. He wrote Shadow and Act and Going to the Territory; and his second novel, Juneteenth, was never completed. But famously, as he was working on it and delayed and delayed and delayed, it was like the whole manuscript burned in a fire. And, when he passed, he had 2000 pages that sort of got coupled together into two different books. One was Juneteenth and one was like Three Days Before the Shooting. And, I think actually Invisible Man becomes the rare, single book that I do think stands the test of time. And, reading it this time, I recognized that it says things to me that I didn't notice the first time I read it, but also that I haven't necessarily heard other people say, which is like deeply fascinating that I could find something in a book that not only did I not notice, but in listening to podcasts and reading reviews, I hadn't noticed other people noticing. Russ Roberts: Yeah. A picaresque, I think, is a series of adventures that a character goes on, like almost a travelogue. It's a very peculiar book. It's not a normal novel at all. The character's personality is not, quote, "normal." We get deep, deep access to some of his inner thoughts. And, we miss--he decides not to share a bunch of others. Let me say a little bit about Primo Levi. Oh, and I think the cocktail party word for a coming-of-age book is a bildungsroman, which is good if-- Dwayne Betts: Yeah, I couldn't pronounce it. Russ Roberts: Yeah; well, neither can I. So that's my shot. But, anyway, it could be handy in, like, a crossword puzzle. I don't know. Primo Levi was a chemist. He's Italian. He was deported to Auschwitz late in the war. I think 1943, 1944--around 1943, 1944. He spends, I think, 11 months in the camp. Survives. Is part of the liberation of the camp when the Russians come. And, If This Is a Man is a searingly unemotional look at the human beings thrust together in the camp. It's really a powerful book. And, then The Truce is about how he gets home, back to Italy from Auschwitz. Which you'd think would take about a week, maybe, or a few days. But, instead, I think it takes nine months. It's a harrowing, heartbreaking book; also very funny in parts. As an economist, I'm fascinated by the relentless amount of bargaining and barter that takes place in that book. There are a number of characters in that book who just like to make a deal. And, they're just going to argue with somebody about--they'll sell a shoe lace or a chicken wing. It's an unbelievable book as a illustration of Adam Smith's line about man's propensity to 'truck, barter, and exchange.' But, ultimately, I found it--in many ways, it's almost as sad at as the first volume. Which is hard to do. Primo Levi gets home. He eventually writes a number of books. The most well-known after these two is the one called The Periodic Table, drawing on his chemistry experience. And, it's also a different kind of memoir. It's a wonderful book. I really like it. And, he dies in 1987, having fallen down a stairwell in a death that is ruled a suicide. And, we'll probably talk about that at some point. There's quite a bit of evidence that it wasn't a suicide. But, I just want to mention before we start that I think a lot of people have an emotional stake in it either being a suicide or not a suicide, as if somehow people argue that he let us down. He survived Auschwitz, but then he killed himself and the Nazis got the final victory, some people will say. And I find that so horrifying and so disrespectful. But, I just want to mention that there was a wonderful article by Diego Gambetta in The Boston Review, looking at the evidence that it was not a suicide; and readers can check that out for themselves. But, the truth is, it's not important in many ways. Primo Levi is immortal and these two books make him immortal. Dwayne Betts: I should say one more thing about Ellison that I think just listening to you talk about Primo Levi reminds me of. It's easy to forget that he's a chemist. It's easy to sort of forget the alchemy that happens to transform a chemist into a poet. And, I was thinking about this essay that Ellison wrote is called "The Little Man at Chehaw Station". And, essentially what happens is, at the time Ellison is working delivering papers or something. And he goes to knock on a door, and he hears voices. And, the men inside are talking about opera; and not just talking about opera in the way a novice would, but they're deeply debating things that different people do within the art, and contemporary singers and performers. And so, he doesn't knock; he's just listening. And then when he finally goes to knock, he falls in and the door's open, and it's all of these black men in it with a soot all over their faces. And, he's astonished because he's thinking, 'This is not who I would've expected to have that conversation.' And, the essay becomes corrective, like a lesson on not to confuse who we think will have knowledge, and always remember that it's this group of people who are deeply invested in something that you care about, that you can't predict and you can't name. And, that was my response to reading Primo Levi's book: because, honestly, I got this strange relationship to books in general and philosophy; and that I'd be the kid that talked too much and the teacher would, say, see me reading. And, I would ask a teacher--I had this long standing habit of asking strangers what they're reading. And, I asked my 10th grade history teacher, what was he reading? It was A Jewish Cat [? Maybe The Rabbi's Cat?--Econlib ed.] And, I wouldn't even even known what that meant back then. And, I only knew him a little later, because I asked him--it was a philosophy book. He let me read it. And, then later on, he was trying to organize a field trip to the Holocaust Museum, and the school wouldn't let him. And so, he asked a bunch of the students, if we really wanted to go, we could go in the summer. And so, he took us in the summer, and that was my first experience at the Holocaust Museum. I had this teacher--I was in 10th grade, it was summer of 10th grade. So, it's the summer before I went to prison, he took us to the Holocaust Museum. And, I'm not going to act like it was like deeply moving and sort of transformative, but it was, like, 'Damn, human beings do this to each other.' And, it was deeply unsettling. And, actually, I was too young to have the information to process it in a lot of real ways. And, I clearly wasn't able to connect what I learned and what I saw to what I might do, myself, on a much lower level. But, still, the kind of brutality in which we treat our fellow people. And so, returning to Primo Levi was a bit of a blessing because it helped me think about: how do you write your way through hardship? And, it helped me, the struggle of every memoir, I think, is that: how do you not be the hero of your own story? And, this was a stunning description of a story in which the writer almost effortlessly resisted being the hero of the tale. |

| 13:35 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. It's funny. I'm really glad you mentioned that first part about the inhumanity of human beings at times. And, very early in Invisible Man. And, I've been encouraging listeners to read both books--all three books--before we start talking about it. [SPOILER ALERT] So, please, if you want, put this on pause. We want to be able to talk about some of the plot and what happens in both books and you should read it yourself before you hear us. But, in the early part of Invisible Man is the scene--Battle Royale, or Battle Royal--that, Ellison finds himself as a young boy in a public fight for entertainment in front of a bunch of rich, white people. And, it is one of the most heartbreaking passages. Again, it's a work of fiction, but it doesn't matter. It's like, how could people do this to other people? How could they manipulate them with such cruelty? And, there's no answer to that question, unfortunately. But it happens. Dwayne Betts: Did you think the beginning--it is interesting, the first couple pages, when he says--this is the part that struck me when I reread it--he says, I am an invisible man. No, I'm not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe. Nor am I one of your Hollywood movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids, and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. When I read it--and the whole book is ostensibly about race in America--but, he said, 'people refuse to see me'. He did not say 'white people refuse to see me.' And, I think on the second read what I found most stunning is that the invisibility is not just a product of race. And, I think his larger argument was, like, the invisibility was a product of the denial of the agency of an individual. And so, even in that Battle Royal, on the second read, what was fascinating is that the nameless protagonist--and everybody that's fighting knows how absurd it is--but they each feel invested in playing their role. And, that role shifts in different ways. Like, their role includes coordinating with each other. Their role includes picking collaborators. The unnamed narrator--the protagonist--he tries to flip one of the white men onto the electrified coins at one point, and then gets kicked in the face for doing it. So, it is like this little sliver of resistance. And, that protagonist wants to give a speech. Russ Roberts: Oh, yeah. Dwayne Betts: And, that was what I found so sad--is that, like, he was, like, 'I still need to get a speech.' And, then it was sort of like, even in giving a speech, it was that moment where he said, 'Social equality.' And, they were like, 'What did you say?' 'I said social responsibility.' And, it was that moment where the assertion of what it means to be, like, human; and it comes out even in the sort of desperate times. Which was, like, ultimately, I believe that's what I appreciated about If This Is a Man. And it was also, If This Is a Man, this is how a man behaves. If This Is a Man, right? As opposed to: this is not a man. And, I think the unnamed protagonist is also asking this question. Like: How do you move through the world if you are a man? And particularly if you are unformed and you're trying to come to some sense of what the word is. You know: How do you respond? And, it is a deeply moral question, I think, that gets asked and answered in different ways throughout both books. |

| 17:46 | Russ Roberts: It's interesting. Both of them, both the narrators, Levi and Ellison are hiding in different ways within their book. Levi keeps a lot of things away from us. As you say, he's not the hero, and he reveals things that are shameful that he's done in the book, but you have the feeling that there's some limit to how much he can reveal about himself. You know, there's that--I just don't want to miss this scene--there's a scene where he gets this incredibly great bit of good fortune. He gets to work in a lab because he knows a tiny amount of--not tiny, but he knows some chemistry relative to the project. And, he and a number of the prisoners who--you know, it's a book, so it's not a video. We see them in our mind's eye: but there's some beautiful women in that office. And he's still a man. And, he's still aware that he's being looked at as a man by these women. And, he still wants to be respected. And, it's impossible. He looks like a bag of bones and he's filthy. And, it's one of the most heartbreaking--there are much crueler things in the book, obviously, that happen to human beings in there. But, his reflection on how these women were perfectly made up, coiffed and dressed, look these German secretaries, look at these Jewish chemists is so heartbreaking. He doesn't tell us everything about what he feels in those scenes, but he doesn't have to. I feel like--it's so hard. We look at it from the comfort of 2022, and I guess we can sort of imagine what it would be like to be in Auschwitz, but not really. You can't. And, I can't imagine what you went through in prison. Again, I can read about it. I can use my imagination, but I think I there's a limit. We can't. Dwayne Betts: You did the episode with L.A. Paul and she talks about a transformative experience. And, I think Auschwitz is a quintessentially transformative experience. And, part of what's revealing about that moment is that it's like: How do you respond to the absolute inability for you to be the person that you want to be in the world? And, the thing about being a survivor and being a witness--and I actually think that Primo Levi is a witness. I think every writer is a witness in some way. But the burden of it is that it's obligation to survive. And so, what we don't know is how he processed the day-to-day to remember that scene. He doesn't reveal that, but you know that it had to happen because there's two ways to respond to it. One way is to let it wash over you as if it didn't happen, to not even notice that you're no longer--to actually embrace being non-human, to embrace what people believe about you. That's one response. But, it feels like his response was to take it all in and carry it around. And, it becomes--it talks about people still bathing, even with cold water and no soap, making their cheeks appear ruddy and healthier because it made you more likely to survive. And, this is--even if this is like a legal[?] fiction, like if we went back in time, it might turn out that: No, this is like the thing you said about correlation not leading to causation. But, what he depicts is the sort of need to believe this, because it becomes one of the sort of building blocks that you use to believe that you're worthy of surviving. And, what you don't get is what it meant to carry all of that horror around and then transform it into something that's beautiful. And, one thing I think about prison--and when I'm reading it, you can't help it, but we, like, analogize. So, I'm reading a book and I can't help but to think about the one moment where you get reminded of how you look in the world, and sometimes it's something as simple as, like, you go to the visiting room; or actually for me now, I got pictures on my desk and people won't be able to see it, but this is me when I graduated from high school. I graduated from the Fairfax County Jail because it turns out I had enough credits to skip the 12th grade. And, they gave me a cap and gown. And, I look at the picture now and I'm reminded of how the wearing a robe wasn't a joyous occasion, because they literally couldn't find a robe that fit me because people my age weren't supposed was to graduate from high school, and people my age weren't supposed to be in prison. So, they just didn't have something that fit a kid that was 5'5" and 120 pounds. And, it's that moment that smacked me in the face. And I'm smiling in the picture, because I'm smiling in the picture trying to think about the sort of--resist. And, I feel like it's not the equivalent of bathing, even though you won't be clean. But, it makes me believe I could understand something of the desperation. And because I think I could understand something of it, it makes me admire the poetry and the lines even more than I would have, I think, if I hadn't experienced some of the stuff I've experienced. Russ Roberts: And, it's a deep question that maybe we'll be able to talk about it. I don't know if anybody can talk about it. What were you going to say? Dwayne Betts: This is what he said, this is what he said-- Russ Roberts: Primo Levi. Dwayne Betts: Primo Levi. Yep. Imagine now a man who is deprived of everyone he loves, and at the same time of his house, his habits, his clothes, in short, of everything he possesses: he will be a hollow man, reduced to suffering and needs, forgetful of dignity and restraint, for he who loses all often easily loses himself. And, you know--and I think--the book, the ability to say that, is the ability to acknowledge that being offended in that moment with those women is the insistence that I haven't lost all. I haven't lost the desire to be a man amongst women. I haven't lost the ability to recognize the shame that others should feel for condoning this set of circumstances. Russ Roberts: And, you're reading that and you think, 'Oh,' because you're reading it in 2022 and you're thinking, 'Oh, surely those women must have felt sorry for him.' And, they didn't feel sorry for him. They didn't see a human being. They saw an animal. |

| 25:45 | Russ Roberts: And, I think it's true of--I feel like--it's funny; I have no right to talk about it, but I'd like, if you want to talk, to hear from you a little bit about the black experience that Ellison's channeling. I mean, the book is so freaking timely. It's so sad how timely it is. There's an Eric Garner moment in the book where a man is simply selling something on the street that's not technically legal and gets shot down in cold blood by a policeman. Eric Garner got strangled, suffocated. He did something wrong, but he didn't deserve death. Dwayne Betts: What's profound about that part is, this guy was, he was a part of the 'Brotherhood,' and the 'Brotherhood' is an organization that that unnamed narrator joins when he moves to New York. But, it's this interesting tension between--and the 'Brotherhood' sort of believed superficially that ideas of race shouldn't be brought up. And they had black and white members, and they would really consistently asked the black members to sort of keep down, tamper down, that notions of, like, racism. And, think about this--basically it's a loosely veiled reference to the Communist Party. Russ Roberts: Yeah. It's a utopian ideal that's loosely based on communism--but not so much on the economics part, more on the revolution-- Russ Roberts: an, resistance to the current inequities and injustices. Dwayne Betts: And, what's profound about it--so, this guy--this guy was the guy who gets murdered by the police. I keep wanting to call him Clifton, but-- Russ Roberts: It is. That's his last name. Dwayne Betts: Yeah. So, Clifton is--so, I think to understand that moment, you got to back up two steps. And, it was a moment when Clifton and Ras, the exhorter, they was fighting. And Ras, the exhorter, represented white people are evil and we should completely separate from white people. And, he believed that Clifton and the unnamed narrator and any black folk that were part of the Brotherhood were traitors. And so, they were fighting in the street and Ras got the upper hand on Clifton. And Clifton was a fighter and a big guy. Ras got the upper hand and started to stab him; and then started weeping, and said, 'I won't do it. I'm not going to stab my brother.' And, he was, like, 'Why are you running with them?' So, you fast forward in the novel and Clifton disappears. And, the narrator finds him on the street selling these Sambo dolls. And, then it's the altercation with the police, and Clifton is murdered by the police. But, the narrator describes him as a man outside of history. And, he was trying to--it is like, what the narrator to me describes is like Clifton was struggling to grapple with the ideas that Ras was putting forth about the world and the ideas that the Brotherhood was putting forth. And, then the Brotherhood had kind of abandoned Harlem as a strategy. And it broke Clifton, and he became a man outside of history because he couldn't comprehend the world that he was living in. And when the officer murders him, you know what was interesting is I actually don't even think that officer operates as, like, a representative of a system. I think the officer operates as another entity that's living outside of history and that's behaving in a way that's, like, unfathomable to anybody that's looking at it with clear eyes. And so, when I read that part, I mean, I find it telling that we still deal with these stories. But I find it telling that we still deal with these stories in a way that kind of avoid, I think, Ellison's bigger point. And I think Ellison's bigger point was that he saw Clifton and Clifton's struggles in a way that the people who were in, and that the way that the police didn't, the way that the Brotherhood didn't, the way that Ras didn't--he wasn't a pawn for the narrator. He was a person who was suffering and who got abandoned and didn't know what to do with the world once that happened. And, that's why I sort of found that part deeply moving. But, you know, I think Ellison is saying something so radically different about race in America than people first think. I was really turned off by the Trueblood scene, at first-- Russ Roberts: Oh, boy-- Dwayne Betts: because I kept thinking that he was creating these archetypes, and that this is how he wanted people to read black sharecroppers. And that he wanted us to juxtapose the black sharecropper with the college students. And, then I realized the integral [inaudible 00:30:43] of that narrative: he was asserting the right for--he said in a letter to Wright--he said that novice, that fiction writers don't go far enough. They aren't ambitious enough even in their absurdities. And, I think what he was trying to do with that is make a bigger point. And to challenge readers to see the bigger point. Because Trueblood says, 'You know what's messed up is, I do the worst thing a man could ever do and that gets more support from white folks than I ever got in my life. I mean, if I had been supported in that way, we would've never been laying in the cold on the floor in the first place.' And so, I think, to me, like, that scene is challenging. But then the other scenes that are challenging is how Ellison insists on noticing the people that we don't notice. And, I think that's what Levi does, too. Ellison insists on when he goes to New York, what is the first thing that makes him become an orator, a speaker? It's a couple being evicted. And, his impulse to speak is both because he sees the couple being evicted as two elderly black folks being thrown out on the street. But also, he wants to prevent the crowd from doing something that will lead to their death. And, who saves him when he leaves, sort of, his first job? And, he's like, he got hurt on a job and they just left him out on the streets and he's stumbling through the streets. It's this woman, Mary, and he sees her and he describes her in such a way in which she comes to life. I think that he animates these individuals, these Harlemites, these people in the community, even the vets, in a way that demands that to be the center of how you think about black life and how you think about American life, maybe at least as much as many of the conflicts animate the novel, many of the sort of tensions animate the novel and the tensions that still exist. I would argue that Ellison probably would say that Clifton's murder wasn't the most significant thing about Clifton's life at all. The most significant thing about Clifton's life was the way the people abandoned Harlem. And, he was trying to fight for Harlem and fight for Harlem in a way that was actually trying to get justice for everybody. I think he would say the most significant thing was what happens when you abandon people. |

| 33:18 | Russ Roberts: Well, the humanity of those characters, like you say, I think, in both books is--it's a great lesson for life in general. That, the idea that: Look around you, there's so many people that people don't pay any attention to. And, we talk a lot in this program about the Adam Smith line, that man naturally desires not only to be loved, but to be lovely. There's so many unloved people. Again, not just emotionally unloved, but they don't get respected, admired, praised. They're invisible. They're hidden. And, we all can look around us and see those people. And, I like to think--maybe it's naive, maybe it's romantic, maybe it's an excuse--I like to think noticing matters and counts. I mean, there are things better than noticing. But noticing is pretty good. And saying hello to those folks in an honest way, not in a pro forma way. Ask them how they're doing. Paying any kind of attention to those people that are neglected, that don't fit in.I think it's a supremely good deed that we often fail to enact. It's uncomfortable. Right? Those people are invisible. The tragedy, of course, is that they make themselves invisible after a while. They're so used to not being seen, they just kind of shrink into the woodwork, into the wallpaper, into the fabric of the world. And, you feel funny sometimes reaching out to them because they don't make it easy for you. They are used to being an unseen. But you have to-- Dwayne Betts: I think the writer, I think Primo Levi is, like, he tells these stories about others to make us see them in a way to push against that. When I read the piece about Lorenzo--and there was this guy that he met and he says: I believe that it was really due to Lorenzo that I am alive today; and not so much for his material aid, as for his having constantly reminded me by his presence, by his natural and plain manner of being good, that there still existed a just world outside our own, something and someone still pure and whole, not corrupt, not savage, extraneous to hatred and terror; something difficult to define.... But, what was beautiful about it, right?--he says all of this. So, he, like, 'Oh man, Lorenzo was great.' And, then he says, somewhere else--he was like, and then he says--where is it at?--he says something else that was like--but it's not even important about the details of the story. He says: The story of my relationship with Lorenzo is both long and short, plain and enigmatic: it is the story of a time and condition now effaced from every present reality, and so I do not think it can be understood except in the manner in which we nowadays understand events of legends or the remotest history. Which, like, which I thought was hilarious in a way, because it was like, this is a deeply--it was these moments that, honestly, I thought nobody benefits from Auschwitz, right? But, I thought that it was this, like, intense moment that lets you see something about humanity that you couldn't otherwise see. And, in a short relationship you could, like, say something profound. But the beauty of those lines was that, in that short relationship, he could both say something profound and concede that, it was nothing special about the relationship. It was kind of like the stuff of legends. It wasn't a deep love. And that is so much of what prison is, because--these relationships, what happens, it's like a relationship in dog years. You know? What happens is, what happens in six months feels like a decade. And, to be aware of that and not romanticize--like, to admit that to the reader--is, I think, it's such a--and you talk about it as what it means about humanity in the world, but just as what it means, just as a writer, I just found it really, really beautiful to be able to convey that. And, I thought it was an act of making visible what could easily be, you know, reduced to--it's a truly tragic book. But, when I think about it, I think about, like, hope and beauty and poetry. And, I don't think it was sentimental. I don't think that, like, it was meant to--I just think it was like, what do we demand of the world that we live in? And, I think we have a choice: it's like, to be lovely. Is that what we demand of the world, that we want to aspire to? And, I think it's so easy to just say, 'No, I want to write about how horrific man is,' and act as if, like, that is the height of intelligence. And that, I truly discovered something by revealing how horrible man is. And, Ellison could have did the same thing, but they both resisted that temptation. Even Trueblood, he says, you know, he said, 'My women, my daughter, and my wife,' and he's impregnated them both. And, you know: maybe he didn't. You know, who knows--but no, I think he did, because his face was sliced open. So, I think Ellison made clear that he did. Right? And, the wife was, like, 'You should just leave.' He was, like, 'But, a man doesn't leave.' Which isn't to make everything that happened before that okay. It's, like, to say that, like--but I can only do what I'm supposed now. Which, I don't know how we respond to that, but I feel like when he wrote it that way, he, too, was trying to not make it seem like it was better, not make it seem like it was a good deed. It was still clearly--it made both characters, it made the unnamed narrator and the guy he was driving around sick--but, I think it was still him saying that--I've represented people in prison who've done horrible things. And, I felt like, you read that passage, and one of the things you walk away with is Ellison suggesting that, after the worst, you can maybe never redeem yourself, but reach towards what you imagine is redemption. Which I think--it's a hard thing to talk about. |

| 40:02 | Russ Roberts: Well, as I get older, I think about that question a lot, of redemption. When I was younger, I judged a lot of people. And as you get older, I think you judge people less. You understand how complicated it is to be a human being. It's ironic. So, now we're talking about people who do horrifying things; and yet they're human beings, too. But, as an artist, as a novelist, in Ellison's case, or a memoirist in the case of Primo Levi, they're capturing human beings in their fullness, and they're not stereotyped, they're not cardboard. That Trueblood scene is a masterpiece. There are many, many--I would call them set pieces, where Ellison--just the poetic flights that he goes on, the use of language, the imagery that he's able to invoke--is so rich. And, in this case, it's serving the humanity of this man--who has done something wicked that he's aware of. He has sort of an excuse, kind of, he was half asleep. He wasn't sure what was happening, maybe. And, but, he's a human being. So, now what? What now? And, he's struggling with that. And, he's not proud of what he did. He's ashamed of it; but can't erase it. And, we've talked on this program a little bit about forgiveness and the challenge of forgiving oneself. And, this character doesn't forgive himself. He's going forward; and it's part of him, what he's done. He knows that, but he moves on, But not fooling himself, not lying to himself, not deceiving himself. He struggles, and he goes forward. Dwayne Betts: I mean, and a subtle critique is of the way society treated him. They're all pawns, in a way. The school wants them gone and doesn't care about the daughter and the mother and the other children. In a white society, it's never clear why they provide support, but even the guy who--I forget his name--but even the trustee that hears the story-- Russ Roberts: Norton. Norton. Dwayne Betts: and gets sick. Norton. You know, he gives him a hundred dollars. You know, it's like, it's just like this idea. But, you know, at the beginning--so that was deeply, like, both troubling, but I think that Ellison was being crafty, in a way, because he was embedding this social critique in a story that was so engrossing that it's easy to not grapple with the complicated, moral questions that are being raised. The same is true--like, this question is: When did he realize he was invisible? He says it in the beginning, but the beginning is the end. Right? So, he says it in the beginning, but that's not when he realized he was invisible. He realized he was invisible when he realized that black people also didn't see him. When he dressed up as Reinhart--and he didn't even know who Reinhart was-- Russ Roberts: That's great-- Dwayne Betts: And, he puts on his hat and the glasses and everybody mistakes him for Reinhart. Like, then, all of a sudden he, as a character, has a moral dilemma that didn't exist. It was these slight notes of a moral dilemma when he was with Sybil. That was a sort of moral dilemma: how do you respond? But that happened afterwards anyway. You know, that happened after the Reinhart piece. But he--he put the hat on and the glasses and everybody mistakes him for this black man named Reinhart, who apparently is a trickster. He's both a well-respected pastor, but he's also a pimp, he's a womanizer and he's dangerous. And, like, all of a sudden he's, like, 'Wait a minute.' If, like, 'You refuse to see me, like everybody refuses to me--' and I think that was also just--the thing that made, I don't want to say it's the thing that elevated the book, but it's the thing that I've never heard about the book. Like, that people said, 'Wait a minute.' The narrator recognized that he was invisible. He recognized that nobody saw him when he started to notice that the black people around him didn't see him. Like, if it was that easy for him to become somebody else, they never knew who he was in the first place. If it was that easy for him to just change his name and leave it behind, like then maybe he never had a name. And, that's the part that, when I read it this time, when I recognized the moral dilemma that then that narrator was in: because he was like, okay, now this is what I'm going to do. I'm going to destroy the Brotherhood from the inside. But he couldn't bring himself to do it. He couldn't bring himself to take advantage. And, so, well, mind you: He had already had an affair with a white woman early on. So, it wasn't sex. It was that the first relationship was clearly consensual and it was based on a kind of mutual attraction. And, you know, he left that [inaudible 00:45:28] in kind of a shame when the woman's husband comes home and he believes, sees him in the bed with her. With Sybil, he sets her up. He has the whole plan. And then he--and it's really a--and you talk about the sixties, and she wants him to brutalize her, to act out some sexual fantasy. This is like a really charged scene, especially when you couple it with the fact that he is thinking that he'll go along with it for his own nefarious purposes. And, then he's, like, 'I can't do this. No, I'm not going to do this.' So, it's an interesting book in the way that it sort of unravels and reveals itself and forces you to question. My first--I read it a time and a half this time. I read the whole thing and then I read 50% of it again and I jumped around back and forth. And, at first, I didn't know what was going on. But I knew what I thought was going on. Russ Roberts: It's hard to follow. Dwayne Betts: And when I went back--and I had to go back and spend some time with it, like, 'Am I responding too harshly?' And, when I went back and spent some time with it, I realized that it was sort of moral dilemmas that were revealing themselves in a way that was far more complicated than I wanted to give any book credit for in the front end. Because, how can a book--because, you know, he doesn't end underground. Russ Roberts: Correct. Dwayne Betts: He ends, like, 'I got to pull back. I got to go back out in the world.' It's almost like The Truce is next. Russ Roberts: Right. Dwayne Betts: You know: How do you go home after all of this knowledge? But we don't get it from him. |

| 47:06 | Russ Roberts: So, what you're saying reminds me of--I hadn't thought about it, but the first part of the book is just so unrelentingly depressing in an Invisible Man. Everything goes wrong for this kid and it's horrible. And, he's abused in all kinds of ways, treated unfairly by blacks, by whites. And, he finally gets what seems to be a good, a piece of good luck. The Brotherhood singles him out. Jack, Brother Jack, sees him and goes, 'Oh, you've got potential.' And, I don't know about you, Dwayne, but I'm reading it, I'm thinking--and I'm not a communist; it doesn't matter. I'm so happy for the narrator that someone has seen him. Seen him. Sees the potential, sees a role for him. And, the narrator, of course--by the way, the--up until then, and it permeates the whole book--we haven't talked about this--he's constantly unaware of how to interact with people. He can't trust them. He doesn't quite understand them. He's always in the dark. And it's heartbreaking. Right? We're rooting for him most of the time. And, he's clueless. Right? And, what's brilliant about Ellison is that we know, we can see who is trustable and who isn't. We can see it. But, the narrator is always lost, especially when it comes to New York. He's this kid from Alabama and he's in New York. New York is a challenge for anybody of any race. But, especially for this, this poor black kid from Alabama, who has just been brutalized emotionally by people he used to respect and trust. And he doesn't know who to turn to. And so, finally--finally--there's somebody who sees him as a great--as a person of potential. Someone who can grow. Someone who could achieve something. And you get excited for him. And, of course, deep down, I guess in the back of my mind--and I probably would've told you, I don't think this could turn out well, but I didn't want to even think about it. I'm rooting for him so hard. And, of course, Jack's a horrible person. He's a objectifier. He sees the narrator as an object to be used rather than a human being to be treated as a human being. And it's--the treatment of, of the inhumanity all around him, is universal. But, the race part, it's ironic. I think it's true of Levi, also. I'd be curious of your reaction. It's very particular. Right? Primo Levi is a Jew, and the Nazis wanted just to kill every Jew. And the narrator of Invisible Man is a black man. It could have been a story about a poor white kid who tried to go to New York. He'd have a lot of unpleasant experiences, also. You could write it that way. But his blackness, especially the tension between the social activism of Ras, the exhorter, who is a black nationalist, and the Brotherhood, which is this idea of universal colorblind justice makes it so much more powerful. And, even though I can't fully relate to it, the book makes me try. Dwayne Betts: But, and, it's also what he wanted, though. Because what he wanted--so, what he wanted from Ras-- Russ Roberts: The narrator? Dwayne Betts: The unnamed narrator. What he wanted from Ras and what he wanted from the Brotherhood was really the same thing. Remember at the end when the riot is going on? And, you know: you saw some of the profound ways that race operated throughout the book--whether it was when he was working at the factory, and he said, 'How do you make the perfect white paint? Three drops of black.' It was like, you know--it was a lot of, like, these subtle-- Russ Roberts: It's an inside joke. Yeah, yeah-- Dwayne Betts: And so, like, you saw this tension that was rooted in race. And it was so rooted in race that the internal racial conflicts became absurd to the narrator. But, for us reading it, it was very real. It was like the person who was used to break the union forming, you know. Or, it was the Brotherhood using Clifton and using a narrator to break the power and influence of Ras-the-exhorter. But, what the narrator wanted was something different. Like, he wanted to recognize the really particular problems of Harlem and address them and confront them along racial lines. Not to pretend like the racial lines didn't exist, but to confront him along racial lines: But, imagine that there was some unified way to do so, that you didn't have to be a nationalist organization to care about issues amongst black folks. And, he would say, 'Oh, Jack, but we can't abandon them. We can't leave them.' And, like, interestingly enough, when he went uptown and he was working on the women's issues, you know, he did the same thing. And so, I feel like what Ellison wanted--what I walk away believing--is that the hope in it is that the narrator believed that it was something possible in terms of justice that you could get without color blind notions of how injustice operates. And so, that's the thread. And, I think that's the thread that remained, even at the end, when it was the riot going on. And, at first he was fooled[?]--he was in it. He was, like, 'This is a riot for Clifton.' And, then he realized it wasn't a riot for Clifton. It was a riot for the accumulation of indignities. Right? But, he also realized that the guy beside him had a gun with one bullet. That: You're going to die. Like: Get out, man. This is not an effective way to try to create change. And that becomes the center of--and, you know, I think Ellison is, like, when Ras-the-exhorter becomes Ras the raptor[inaudible 00:53:38], it is about the futility of certain kinds of nationalism, and how you end up--you could say it's like France Fernand talking about how you become the oppressors, like, how you end up eating yourself. And because Ras-the-exhorter becomes Ras-the-destroyer and is now suddenly willing to kill the unnamed narrator and is launching a spear at him. And, I think that's, in terms of the contemporary moment and why Ellison is so, I think, relevant now, is because he's arguing that those tensions exist. It's: How do you shape out, how to reimagine America, how to reform America, how to make America better? The tension is still the tension between Ras-the-exhorter and Ras-the-destroyer, and sort of the narrator: How do you different pose a belief, operate in a world? And a tragedy of, like, what would it mean if we stopped believing that there's a possibility to come together and actually support this community, having a better shake at it? So, I don't know. I was troubled on a second reading of the book because I realized you don't think idea-books should keep mattering. Maybe we do think idea books should keep mattering; but I wanted to read it and believe that somehow we had lapped[?] some of the questions that he raises. But we really haven't, like, lapped many of them. And, I think some of us have become more ingrained in a sort of Ras-the-destroyer side, you know--more entrenched in the Ras-the-destroyer. |

| 56:27 | Russ Roberts: Well, there's always this temptation, I think--a related issue is when the narrator eulogizes Clifton. It's an incredible eulogy. And you want it to be this sort of emotional--I want it to be this uplifting tribute to this man. And, it's not. It's real. It's so real. It's so powerful, about the loss of a life cut short, and too soon. And, it's just--it's a spectacular piece of writing, to me, because it's not what I--he could have written something really different. And he gets skewered by Brother Jack because he actually had a human moment. He just eulogized a man. And, it really is ironic, given our pairing here: If This Is a Man. And that's what Clifton--that's Clifton's eulogy is--that this was a man. And the Brotherhood wants to treat him as pawn and wants to treat the narrator as a pawn. And, I think our current moment of race in America is this tension between our ideologies, which we all have--whether we know them or not, almost all of us have some kind of ideology--and the human moment. And, if you're not careful, all you do is, I guess, the human moment and you don't get any change. But, if you're also not careful, you treat everybody like a pawn and you're not a human being yourself, anymore. Russ Roberts: I think I've talked about it before on this program. I know I have. I can't remember the episode. Maybe it'll come to me. But, Vasily Grossman has a essay on Treblinka that is deeply chilling--another death camp of the Nazis'. And, he actually argues that the Nazis, in those settings, couldn't killed the prisoners. They could just kill themselves. They could murder their own humanity, but they couldn't take away the humanity of their victims. Again, a little bit romantic, perhaps, maybe sentimental, maybe unrealistic. But, he says that in his other book, Everything Flows, another great book he wrote, incredible book. |

| 57:51 | Dwayne Betts: But, do you think--and I think this is one of the challenges for Levi--this is one of the challenges for anybody that writes about the Holocaust--is that it's very easy to just say that, like, the victims were pure. Like, the Jews were pure. It's like, because the Nazis are so horrible, that it's easy to just sort of frame the conversation that way. And, I wonder--because, you think about criminals, nobody says that. If you're on death row for something, like, nobody says that--you know, we have a horrendous system of incarceration. I'm not comparing-- Russ Roberts: No, I understand-- Dwayne Betts: the Holocaust-- Russ Roberts: I understand-- Dwayne Betts: But, no, I'm thinking about people listening. People listening might be, like, 'There he goes.' But, no--because I often ask people, is the question not 'what does a person deserve,' but, like, 'what do we have the right to do to them?' And, I feel like that's what the narrator's constantly asking. You know. And, it's that moment where Ras is saying, 'You deserve to die. You were just trying to kill me. But, what do I deserve to do to you as my brother? I do not--I don't deserve to kill you.' 'Like, I refuse to do it.' And, then something transforms in him; and he becomes less than himself, where now he's willing to kill the narrator. And, I just wonder if--the beauty of, I think, of any, like, great piece of literature is that it refuses to make my right to live, my right to be loved, my right to be noticed a product of my purity. And, I think that that's what Levi did, and that's what Ellison does. But like, frequently, in the popular conversation, our ideologies force us to assert the purity of our roles, of our positions, because it is that purity that justifies doing anything--you know, rhetorically, or sometimes actually physically--to defeat the other side, you know. |

| 59:56 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. I don't know what to say to that, Dwayne. I think that's exactly right, though. I think about--there's a concept in the Holocaust literature, and here in Israel--the Righteous Gentile. And the Jewish community honors Righteous Gentiles: the very formal honorific, it means that, during the Holocaust, you sheltered Jews or you took risks and saved Jewish lives. If you go to Yad Vashem, which is the museum here, the Holocaust Museum here in Israel, these people get named. There's an honor roll for these folks. And, it's hard to think about whether the list is long or short. You know? Would I have--if I were a non-Jew in Germany, Poland, Hungary, Italy?--would I have sheltered a Jew, endangered my own family? Why would anyone--how could anyone do that? Yet they did. And, then you could ask: How could anyone not do it? But, of course, most people can't. And, there's so many--and you talked about the purity of the Jews, a huge issue in Jewish literature on the Holocaust of the Jews who collaborated with the Nazis in the camps. Levi writes about it. Do you blame them? I can't. I don't know what I would've done under those circumstances. I have zero confidence in my own ability to rise above my urge to stay alive. Dwayne Betts: Levi certainly doesn't blame them. That was one of the things I found astonishing and so impressive in the way in which he paints some of those pictures. And, again, it's not sentimental. It's just somebody who was there saying, 'Sometimes I made some tough decisions, too.' I think that really, like, great literature should make you, should move you to the point that you are almost absent of response. And, I do think some of them take more thought to get you there. I think Levi is, like, it just cuts to the quick, based on the subject matter, based on right. It really is just so charged that you approach the page and it's hard. And, I've read other books that--we sent 1500 copies of Frankl's book, Man's Search for Meaning. But, even in the title--but, I mean, it's a good book. Some of it, the first half, I think, is lovely. Right? And, still though--and[?in?] it's moments that reach to, I think, the best moments of Levi. But, as a whole, I stopped reading it. And it's not that I stopped reading it because I didn't think it was good anymore. I stopped reading it because it became--towards the second half of the book, it became just not the same thing. And so, it is not that you guarantee to do the thing you take on a subject matter. And, I think this is what I mean: like, the book moves you to a point where you see something of yourself--you see something of who you aspire to be and something of who you aspire not to be within the pages. And, I think that's when a book really, really does something for you. It becomes less about informing you and exposing you to a world that you hadn't seen, but it becomes about, in a really private way, bringing you into that world. And, I think that's what Ellison does. And, the beauty of it, the strength of it, the craft of it is when--it tells that story about the man who was locked up for 19 years and he escaped, and he gives him that leg iron. Russ Roberts: Oh, God. Incredible. Dwayne Betts: And then, because he doesn't want to make it easy, he has another black man come into his office, like, 'What's that you got on your desk? You shouldn't show people that. You shouldn't make people remember that.' And you know: the narrator didn't want it actually. He only took it because he thought--he planned on throwing it away. And, it was almost like Ellison showed us the narrator being educated in such a way that we became educated about what it means to sort of hold on to history. And, all of a sudden, I didn't know who I was in that story. I didn't know if I was the person that wanted to hide my past. I didn't know if I was the person that escaped from prison or if I was the person that just accepted something, because I didn't know how to reject it. And, I think that's what--but I was there. I was actually all of those three at various moments. And so--this is why--my wife told me I can't go back to college. But, this is why, even in my moments of wanting to be an economist, of wanting to sort of like deeply understand markets, and ask myself, 'Can you be an economist and think about the world without being so entrenched in numbers?' The reason why I often find myself not wanting to be whatever we imagine to be a scientist is because science is obsessed with the resolute-- Russ Roberts: Yeah-- Dwayne Betts: and the provable. And, art is obsessed with the notion that, like, if you weep, that's the only evidence that matters. If you're moved, that's the evidence that matters. And, it's a weird tension in my own head about how to make those things coexist, because you can become a person that doesn't truly try to find ways to fix problems, because you only know how to talk about them movingly, if you don't think in some concrete ways. But the narrator was doing both. He was giving the speech for Clifton and also organizing. And so, I think in that way, the narrator was believing that you could do both. And you could do both premised on the idea that that notion of universalism can exist without ignoring the fissures of race and without ignoring the realities of race. Which I think is something that's deeply important for me to believe as a increasingly--I'm, like, 41 with children. It's something really different to be 20 and not feel like you got a stake and responsibility in your community. But now I feel like I should be doing, like, at the very least--I do vote, but it's like at this moment, you feel like at the very least, if you see somebody being evicted, you shouldn't just walk past them on the street and not notice that this is a whole life that's thrown on the sidewalk. And, that's Invisible Man making me think that. And so--I don't know. |

| 1:07:11 | Russ Roberts: Well, you're not alone. There's at least one economist who has that tension between the resolved and the ambiguity. It's something I think about all the time. Right? A lot of people--especially being the president of a college that's devoted to the great ideas of Western and Jewish thought--I mean: 'Come on, you got science, or what about biology, computer science, engineering? Let's do stuff. All that art, literature, and philosophy do is make you weep.' But, I think they also make you wise--if you're lucky and if the art's good. And, I think that three-headed moment you had--three-hearted, I guess, a better phrase--of feeling like the person who wants to hide his past, the person who wants to remember the past, the person who wants to emotionally cope with it and try to make it part of who a person is--all of that should be who you are as a full human being. You don't want to be a cardboard character. It's a huge issue here in Israel about the Holocaust. It has been for the last--since the establishment of the state in 1948. Right? Here you have these Holocaust victims, who are small and ineffectual. It's one way to summarize them. They're victims. And, then the state of Israel gets established, and the ethos that Israelis want to have is: 'We're warriors. We're not like those European Jews who sat around reading the Great Books for hours a day. We're strong. We're not afraid of anybody. We got nothing to worry about except defending ourselves.' And, it's a fascinating, I think, moment in human history, that transformation of the Jewish people from this intellectual, ineffectual, victim class--it can't be much worse than 6 million people dead in the Holocaust, to--one of the greatest military, absurd, overcoming-of-odds in both the establishment of the state in 1948 and the War of Independence, or the Six Day War in 1967. And so, Israelis, I think, have an issue with the Holocaust. It's hard. It's hard. And, a lot of people--I was at a gathering that the night--said--this is a big issue in Judaism--was, 'Holocaust, Holocaust, enough. We got to look forward. We can't look back. Can't look at that past. If that's all we are is victims, then young people are going to get a terrible image of what Judaism is about.' And I certainly think--I'm somewhat sympathetic though I hate the, 'Let's compete and see who's the worst victim.' 'Let's try to--I got mine, you got yours, let's see whose is worse.' And, I think that's a horrible mistake. But, coping with the past--either the past of one's people or the past of one's own life--and how you should look back and deal with that, or ignore it, is, I think, an enormously important part of the human experience. And, it's not just about weeping. It's about knowing who you are. And, certainly who you are is partly where you came from and it's where you want to go. That's one of our great gifts as human beings: we can look to the future. And I don't think you can ignore it. And, I think the richness, the non-resolute, the non-resolved aspect of the human experience is enormously important. And, I think it gets neglected by an over-emphasis on science and precise results and three decimal places. I love this line from Picasso: [?], like, he said, 'Computers are useless. All they give you is answers.' Dwayne Betts: When you asked me for a book, though, that was my tension. It was sort of, that, like: Enough about the Holocaust. I thought, like, 'What book will I choose?' And, I was thinking about Wright, because I was reading it in the moment-- Russ Roberts: Richard Wright-- Dwayne Betts: Richard Wright's Black Boy. And I chose--and I was like, 'I don't want to do this one,' because I thought that he had a really clear sense of the world. But, it was 1930s Mississippi, but I thought he wasn't as generous to the people around him. And, I just thought it wasn't a good thing to read in company with--I didn't want to read it in company with If This Is a Man. And so--and then I thought, 'Man, but am I going to choose a book that talks about race, because is this the only thing that we could talk about to understand what it means to be black in America?' And, then I started thinking about the Freedom Library and the idea that arguing that Invisible Man is important in a way that it treats issues of race is important, is not suggesting that there aren't another 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 500 books that we could be reading. And, I think it's the same thing for If This Is a Man. It's like, in my head, I wonder if I reduce what it means to be Jewish to the Holocaust. And, then I think, 'No, I mean, I don't. I read The Chosen. I've read a few other books, you know; and I connected with The Chosen.' I mean, I, literally--when I got hit in the eye with the soccer ball, I just thought, 'Oh man, this is just like that book I read.' And, it was my solace as I was being rushed to the emergency room in handcuffs, because they thought that I had a detached retina. And so, yes, I buy that point. And I also believe that part of the struggle, at least for me, is finding ways to sort of deeply tap into other cultures of the world. And, you can never do that through a math problem that just gives you answers. You can never do that through science. But you can do that through literature. And, maybe that's why I appreciate EconTalk, because it has this belief in books as literature. Even in books that are sort of deeply rooted in different ways and economics, they still come off the page and within the conversations as literature, because it's always like a story that is animating the numbers. It's not the numbers that animate the stories. It's the stories that animate numbers. |

| 1:14:12 | Russ Roberts: So, let's close with this question. And, then maybe at the end, you can give us a little update on the Freedom Library. So, one of the things that was special about reading this book--and I told you before we recorded; I'll share with the listeners now--I started the book and it's so depressing, the first couple hundred pages. I'm thinking just everything goes wrong for the narrator. It's unfair. It's really unfair. It's like too much. And, I'm thinking, 'Why did I agree to read this? It's just depressing. And I get it.' And, having said that, as we suggested, there's innumerous set pieces in this first half, quarter, 40% of the book that are unforgettable. Magnificent. And, at least unforgettable for me now that I've read it a week ago. And, then I forgot about them when I read it when I was 20. But, they're fabulous. And, the book then just rises up. It just goes from being a picaresque novel of a pitiful, abused character where nothing goes right to an anthem about all the voices in America, all the tensions that we've been talking about between races and whether we should--what we should be striving for, what's the right way to get there from here. And, I finished the book this morning. I take a bus to work sometimes. I sometimes walk. And, for reasons that aren't worth going into, I got off the bus early, and I was going to walk the last 15 minutes to work. And I just stood there and read the last 15 pages on the sidewalk, standing, on my phone. And, it just filled me up. It's really an incredible experience. But, part of this fun--not fun; fun is not the right word. Part of the emotional kick of reading this book as a 67-year old instead of a 20-year old was reading it with you. So, I had you over my shoulder. And of course, I have to wonder--I can't read this book the way you read it. And, similarly, while you were reading Primo Levi, I'm sure you were wondering how I read If This Is a Man. I cried when I read the Primo Levi at the age of 65. I'd read it--again, as a kid. And, I cried. There's--there's one line, I'm not going to say what it is, but there's a line in The Truce--comparing the two books you would've picked, usually If This Is a Man. But, in The Truce, there's a line that just broke my heart. And, I don't know: Is that because I'm Jewish? Is that because I'm a person? But, I'm sure when you're reading those two books by Primo Levi, you're reading them a little bit with me over your shoulder. And so, it made it much more special for me to read it alongside you. I didn't know you were going to go back and reread Invisible Man. That makes it even sweeter. But, to read these two books--these three books--together with our different backgrounds and our different emotional responses--because you're black and I'm a Jew: it doesn't matter. We're just two different people, going to read them differently, no matter what. But, it just made it, it was exhilarating in many ways. I'm grateful to you for it. And I really appreciate that you agreed to talk about it on the air. Dwayne Betts: When you suggested Primo Levi--the book is falling apart. It came to me and it's one of those books that, you know, like, you might get a bad copy buying it, because it's both of the books together. And, it was falling apart, but it became a whole experience. You know, it was--the pages were falling apart, but the ideas were so cohesive that they was just sort of becoming a part of my life and a part of my conversation. And, I'm telling people about Levi. I've got this habit of telling people about things as if they hadn't read it before. And, I've got a bunch of Jewish friends and I'm like, 'Yo, you read Primo Levi?' And, I got a bunch of friends who hadn't read it. And, I'm talking about, 'This is the book that'll make you think about, like, prison in a different way.' Which is not the thing that you expect somebody to say about Levi. But, I thought that I was reading it with you over my shoulder. But also I was reading it with you telling me that it would help me understand something of the Jewish experience and then astonished in a way in which it reminded me how literature helps you understand something about your everyday active experience of trying to be a human being worthy of being loved in the world. And, when you suggested that I suggest a book to you, one of the struggles was figuring out what book it was. And, then I chose Invisible Man. And, then I was afraid that it was the cliche choice. And, I knew I hadn't read it since I was like 16 or 17. And, I actually didn't remember much of it--also. And, it's weird because it's the kind of book that matters when you read it and you talk about it. You know, the narrator--I don't know if he changes much from the first page to the last page. I think the narrator starts out saying, 'But, why would I lie to Mr. Norton?' And, I don't think it's like, 'Why would I lie to this white man?' I think it's like, 'You don't lie to people.' And so, he ends the book at that same sort of innocence. It's horrific because at the first parts of the book, you think this would just be better for him if he distrusted everybody. And, when he takes on the Reinhart persona, he starts to think this would be better for everybody if I distrusted everybody and was just manipulative. And, then he abandons that. And, reading it the second time made me believe--you know, that--about different manner or possibilities in the world. And also, this is the wild rift, though. It says: 'Iam invisible because you have refused to see me.' And, it's like: You. And the You is Me, and the You is You; and You as the reader. Right? And, it ends with 'Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?' Which is to say, I speak a kind of possibility for who we might be. That is radically different from both who we had been and who we had been at our worst. And so, it was a real honor and a pleasure. And, I will say, right, like: we talk about reading it together. When I was talking to these guys, I put the Freedom Libraries, one was in a segregated housing unit. And, when I was in segregated housing unit, solidary confinement. When I was in solidary confinement, I was in there for like five different times. But each time it was because they said I did something. Whether or not I think it was worthy of being put in a hole or not, it was always because they said I did something. And so, when the prison said, 'Will you put one in solitary?' I thought, 'Yeah.' And, I thought it was for people like me who had ostensibly done something to get put in the hole. And, it ended up being for a group of guys who were roughly in, like, protective custody. And, I got a chance to talk to them. And, one of the things they said was the reason why books matter--it's not just the reading, but because we can have conversations like this. And, I think that that's what you could do around books--that you can do around stories, you can do around narratives--that allow us to see each other in profoundly different ways. That just is the one technology that I think truly distinguishes us--at least I imagine distinguishes us from every other species. It's the one unique thing about being a human is that we could tell each other stories and those stories allow us to think differently about who we are and who we might be. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Dwayne Betts. Dwayne, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Dwayne Betts: It was a pleasure, always a pleasure. I'm chasing Mike Munger though. I'm at two. I'm going get to 150 before 2027, so he better keep coming on the show. I'm coming for him. Russ Roberts: I've got bad news for you: he is coming soon. But, it's okay, I'll have you back. |

In his memoir of his time in Auschwitz, Primo Levi describes Jewish prisoners bathing in freezing water without soap--not because they thought it would make them cleaner, but because it helped them hold on to their dignity. For poet and author Dwayne Betts, Levi's description of his fellow inmates' suffering, much like the novelist Ralph Ellison's portrayal of early twentieth-century black life in America, is much more than bearing witness to the darkest impulses of mankind. Rather, Betts tells EconTalk host Russ Roberts, both authors' writing turns experiences of inhumanity into lessons on what it means to be a human being.

In his memoir of his time in Auschwitz, Primo Levi describes Jewish prisoners bathing in freezing water without soap--not because they thought it would make them cleaner, but because it helped them hold on to their dignity. For poet and author Dwayne Betts, Levi's description of his fellow inmates' suffering, much like the novelist Ralph Ellison's portrayal of early twentieth-century black life in America, is much more than bearing witness to the darkest impulses of mankind. Rather, Betts tells EconTalk host Russ Roberts, both authors' writing turns experiences of inhumanity into lessons on what it means to be a human being.

READER COMMENTS

Scott

May 3 2022 at 5:16pm

What a great endeavor, and an interesting setup to leverage your experiences and background to help understand someone else’s. I appreciated both guest and host being very patient with each other to allow time for thoughts to coalesce and arrive at the right words. It was a wonderful break from the quick-paced exchanges typical in more academic and economic episodes. Thank you both.

krishnan chittur

May 5 2022 at 11:41am

Enjoyed this very much – fascinating to be able to listen in like this … I learned a great deal about both the authors (and the books) – many things stood out, but what I found fascinating is the ability of some authors to look beyond the immediate and see what others do not see and explain, write about them.

I imagine (and hope!) that we will hear more such econtalks …

AtlasShrugged69

May 5 2022 at 1:23pm

Having spent some time in jail, it’s not something I like to talk about. I view it with shame, regret, and sadness; that the me of 12 years ago could have done such horrible things to such undeserving people. Everyone has some behavior they look back on with regret, and I think society is similar, yet different, in that society continues via new generations, and our individual lives are finite. Our defining moments as individuals, good or bad, remain ever present in our minds. As a society, time marches on, and we inevitably become less defined by our worst moments of the last 100, 200, or 1000 years. New generations are unique and capable of making their own successes and mistakes, and to define these new generations in terms of events well before their time is an affront to their autonomy and capacity as heroic individuals plotting the course of their own destiny. Great episode

Ethan

May 6 2022 at 8:26pm

I was unfamiliar with both of these books. I had heard of Invisible Man, but never picked it up. It is truly one of the best American novels as far as I can tell.

One thing about the invisibility of the Narrator in Invisible Man is that even those ostensibly rooting for him, or those that might be on his, side do not see him. On reflection, I wonder who actually does see him. Mary is a perfect example of someone who has good intentions in her vision of the narrator, she sees him as a future hero of Harlem, as someone who will do great things. She does not see a man with all his faults. He almost goes through a lazy phase in unannounced protest of Mary’s inability to see him as someone who has failed himself in so many ways.

To comment on Dwayne’s point about the other boxers and the conformity in a system that has dehumanized them; I am reminded of Levi’s “Last One.” This is the chapter in which the final public hanging takes place. Levi decries the reaction of the prisoners: “I wish I could say that from the midst of us, an abject flock, a voice rose, a murmur, a sign of assent. But nothing happened. We remained standing, bent and grey, our heads dropped…The Russians can come now: they will only find us, the slaves, the worn-out, worthy of the unarmed death which awaits us.”

Also, I did not mark the page, but one thing that struck me in Levi was a anecdote about a bowl, something that is so precious to the prisoners but to us would be trash. Levi mentions, almost in passing, that he and Alberto scratched their names it in. What struck me is that some had scratched their number in it. This just came to mind as Russ and Dwayne spoke about hanging on to one’s humanity. To continue to identify with your name is something so fundamental in us. It tears my heart to think someone accepted those digits as a peice of identity.

Also, I will just say that I thought the chapter “The Canto of Ulysses” was such a powerful scene about humanity and art and the ability to use art in communication and commiseration and mutual understanding. Given Dwayne and Russ’s background I thought for sure this would be covered, but there is only so much time. Thanks again

Lauren Landsburg

May 8 2022 at 4:18am

My grandparents–my mother’s parents–didn’t have a lot of books in their house. This wasn’t because they didn’t read or value books. In fact, when I was a teen, Grandma became the founder and indomitable force behind the annual, million-book, AHRC Book Fair on Long Island. [AHRC being the Association for the Help of Retarded Children.]

It was because, by dint of Grandpa’s hard work running a car dealership, they became kind of nouveau riche during the Great Depression. So, when they bought their mini-mansion in the late 1930s or early 1940s–a house and expansive property with a name rather than a street number: “Top O’ the Hill”–they felt proud to have even four built-in room-length book shelves in the room we all called the Den. A room that also housed Grandpa’s TV and the green velvet sofa on which we were allowed but discouraged to sit, in favor of the floor.

So, they hired an interior decorator to stock those shelves; and they insisted that the books be “classics.” Mostly that turned out to be books with fresh leather bindings and a lot of gilding. Among them was a whole shelf of the 11th edition of _The Encyclopedia Britannica_, which I think Grandpa, with his photographic memory, had not only read but also allowed me, after big family dinners, to take down and read, one volume at a time, turning pages on the Den floor.

When my brother, Matt [name changed] or I stayed at Grandma and Grandpa’s house, we often slept in what later came to be called “Grandpa’s room.” When we were infants, there was a crib–which I remember sleeping in and remember indignantly having to give up to Matt. It was an altogether amazing room, with a wide, raised window alcove we kids used as a stage to perform shows for the family, and a walk-in closet that had a window. A closet with a window! It was mind-blowing–to use an anachronistic term.

The bed was large and always covered with warm blankets and a pillow-light down duvet. Grandma would sit by me and tell me tales as I drifted off to sleep, and we would listen to the distant train whistles in the night. She taught me to love those prolonged and haunting sounds of the trains in the distance.

Next to the bed, one on each side, were two sturdy endtables. On each was a reading lamp. On one of the bedside tables was a little bronze Buddha. Eventually I asked, “Grandma, we are Jewish. Why do you have a Buddha?” A lovely conversation ensued, to the effect that all religions offer something good, and believing in one does not preclude the protections of others. So, maybe this small Buddha might symbolize and offer me protection, peace, and happiness as I sleep.

But also, the endtables had bookshelves at the bottom. With books that for years I had no interest in reading. E.g., _How to Make Friends and Influence People._ Plus some other book of jokes or humor, the name of which I can’t recall, with one-paragraph anecdotes about adults that seemed completely lacking in humor–at least, to my youthful mind.

And also, next to each other, two books that didn’t seem to belong there: _Color Blind_ and _The Invisible Man_.

Like, I assumed _Color Blind_ was some kind of medical text. Half that side of my family was in the medical profession. Doctors, dentists.

And, _The Invisible Man_–well, when I perused the endtable shelf at some point I thought: “Oh! I get it now! It’s a novel! It must be something like the old-fashioned TV show, _Topper_”.

Now, _Topper_ was more my brother’s kind of thing. But I did relish the show.

So, at some point, I pulled out that book off the bedside table shelf and started to read it. I was maybe around age 13 or 14. I must have been a bit desperate for something to read. Maybe I was staying at Grandma’s house while I was ill? Or maybe while my parents were away on a rare trip?

And the book was riveting.

After the first full chapter or two, I knew I’d gotten something very wrong in my understanding. So I started over. I rarely had ever done that before–started reading a book over. But I realized I was deeply confused and that the whole thing was _not_ some kind of novel about a Topper-like character. It was a wholly different and even more astonishing matter.

And so I re-read it, in a state of half-belief. How could this be? Who in America had to deal with this? Yes, as a young teen I was kind of aware that blacks, especially in the South, had hardships likely beyond my ken. But this book, this Ellison book, _Invisible Man_–the reality it portrayed was not just beyond the ken I’d envisioned, but beyond any ken I could imagine.

I asked Grandma, “Grandma, is this real? Are blacks really treated this way? Anywhere?” And we had a long talk. About the North versus the South. Fiction versus nonfiction. How real, how much was true versus untrue in this book, and how to try to discern that for yourself while you read. The upshot of which was that, yes, it was sadly and shockingly real.